Julie Pickard: drawing the music

If you go to a jazz or free improv gig and see a woman up on stage in amongst the musicians, not playing but drawing, it’s probably Julie Pickard. Julie’s an artist and writer who produces extraordinary expressionist drawings that are a response to her experience of live music. Details of instruments and musicians emerge from the squiggles representing the music on the page. You might be able to decipher the curve of a double bass, the buttons on an accordion or a violin bow. Often you’ll see the feet of a musician firmly planted on the floor.

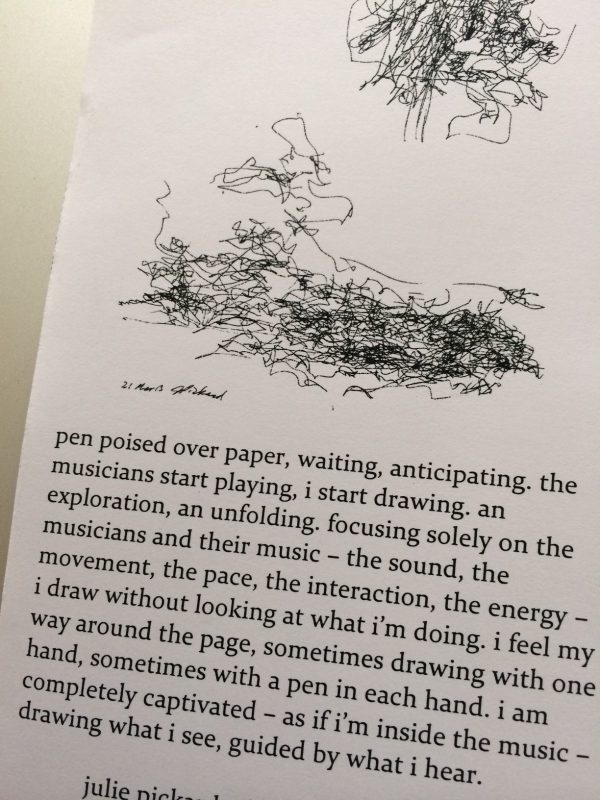

I first met Julie at an Urban Writers’ Retreat and was intrigued by Julie’s card, which shows a drawing together with a description of how she draws without looking at the page.

“Like I’m inside the music”

A few weeks later, we’re sitting in a cafe in Islington and Julie explains her idiosyncratic approach to ‘drawing the music’.

“When I’m drawing, it’s like I’m inside the music. I don’t look at what I’m doing while I’m drawing. I’m completely engrossed. I’m drawing what the musicians are feeling and doing. I get this whole feeling of embracing the music and I always draw live. Although the drawings look abstract, they’re completely representational, because I’m closely observing and drawing what the musicians are doing as they’re playing. Classical musicians are harder to draw because they don’t move as much. When there are two colours it’s because I’m drawing with two hands, either because my right hand is getting cramped or because there’s so much going on I can’t get it all with one hand. I start drawing as soon as the musicians start to play and when they stop, I stop too.”

A bit Bauhaus, a bit Twombly

Over the years, many artists have explored the links between art and music. The Bauhaus school experimented with synaesthesia, looking at how art and music could influence each other. Paul Klee was a musician before he was an artist, and in his lectures at the Bauhaus he compared the visual rhythms of drawings to the counterpoint of J S Bach. The Czech artist Frantisek Kupka and Wassily Kandinsky also produced abstract works inspired by music.

What’s different about Julie’s work is that she draws ‘blind’, looking at the musicians rather than at what she’s drawing. In this respect, her technique is more like Cy Twombly’s night-time sketches. When he was conscripted in 1954, in a bid to free up his drawing style, he drew in the dark. “Someone once compared my work to Twombly’s,” Julie says, laughing.

The cardboard keyboard

Julie’s life in London today is very different from her childhood in Canada, although music and exploring were early passions. She grew up in Etobicoke, a suburb on the edge of Toronto. “It was a poorer part of the city,” says Julie, “and I spent a lot of time playing in a nearby ravine, pretending I was an explorer from another century.”

Her family wasn’t musical, so music came as something of a discovery. “When I was four, I was in kindergarten and heard this tinkling sound. I followed it, opened a door and found myself in the middle of an after-school piano class. They welcomed me, and sent me home with forms for my mother to sign and a cardboard keyboard. So when I was four years old I sat at the kitchen table learning to play the piano on this piece of cardboard.” Eventually her parents bought her a beaten-up out-of-tune piano which she played until she was nine, then switched to guitar at the age of 14.

Although her musical studies progressed pretty well, Julie’s early experiences of art were less successful. “When I was nine or ten, I handed in a freehand drawing project that I’d done at school. The teacher said I’d traced it and screwed it up in front of the whole class. I was devastated. Then when I was 11, we had to draw still lifes using plastic fruit. I’d have loved to draw a real banana, but just wouldn’t draw a plastic banana. My reaction was rather extreme. I stopped drawing.”

Although she’d been turned off drawing, Julie continued making things, knitting, making mosaics and taking craft classes. Having taken a winter out to skate on the canal for the winter in Ottawa, she decided it was time to go back to her art studies. She took her first degree in Art and English in Edmonton, studied at art college in Toronto, then won a scholarship to study for a Masters in Sculpture and Public Art at the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee.

After that, in 1996 she moved to London ‘for three months’ and has been here ever since. Julie now earns most of her living from editing exhibition catalogues for Scala Publishers, the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, other international museums and private collectors.

Pocket trumpet, garden hose and trombone

Julie’s experiments with drawing to music happened by chance. “One of my neighbours played in a free improv group so I started going to gigs at a place on York Way called The Cross Kings. I had a tiny little sketchbook I used to carry around and I just pulled it out and started to draw,” she says. “I’d come from my studio in Hackney Wick on my motorcycle, draw in the dark and go home.” At later gigs, she’d listen to musicians including drummer Steve Noble, saxophonist Sue Lynch, viola player Benedict Taylor, guitarist Daniel Thompson, singer Sharon Gal, among others, and Paul Shearsmith, who plays pocket trumpet, garden hose and trombone.

Bit by bit, Julie amassed quite a body of work. “I used to put the drawings in a box and didn’t look at them again. Then, when I was having an open studio, I spent a day going through my drawings and suddenly realised ‘There’s something going on here’. I’d never laid them out or put them on the wall. I had a big studio then, so I put 100 drawings along the walls in rows, like a quilt.”

At the open studio event, Julie’s music drawings caused a stir. “People were amazed,” she says. “Some people didn’t get it but the people who got it recognised immediately that these were musicians. They said, ‘Wow, this is music.’ Some people were in the studio for ages looking at the drawings.”

Becoming part of the band

Julie was also starting to get more attention from musicians. Originally she hadn’t wanted to disturb them and thought they wouldn’t notice somebody scribbling away in a corner. But, as she admits, sometimes there were only six people in the audience, so she was more conspicuous than she’d thought. Musicians began to ask to see what she’d drawn. Julie gradually got to know the musicians and is now occasionally listed as one of the performers. At a Horse Improv gig on 15 July in Kennington, her name appeared on the flyer along with the musicians’ names. Her credit: Visual Artist.

So what’s next for Julie? “I’ll continue to draw,” she says. “I want to create an artist’s book using the drawings and I want to try working on a larger scale, with colour, and to explore these ideas in oil in my studio. I’ve also talked to a few musicians about wearing a microphone on my finger, so they could respond to the sound of me drawing them.”

An artist inspired by musicians inspired by an artist? That’s a whole new spin on the creative sound loop.