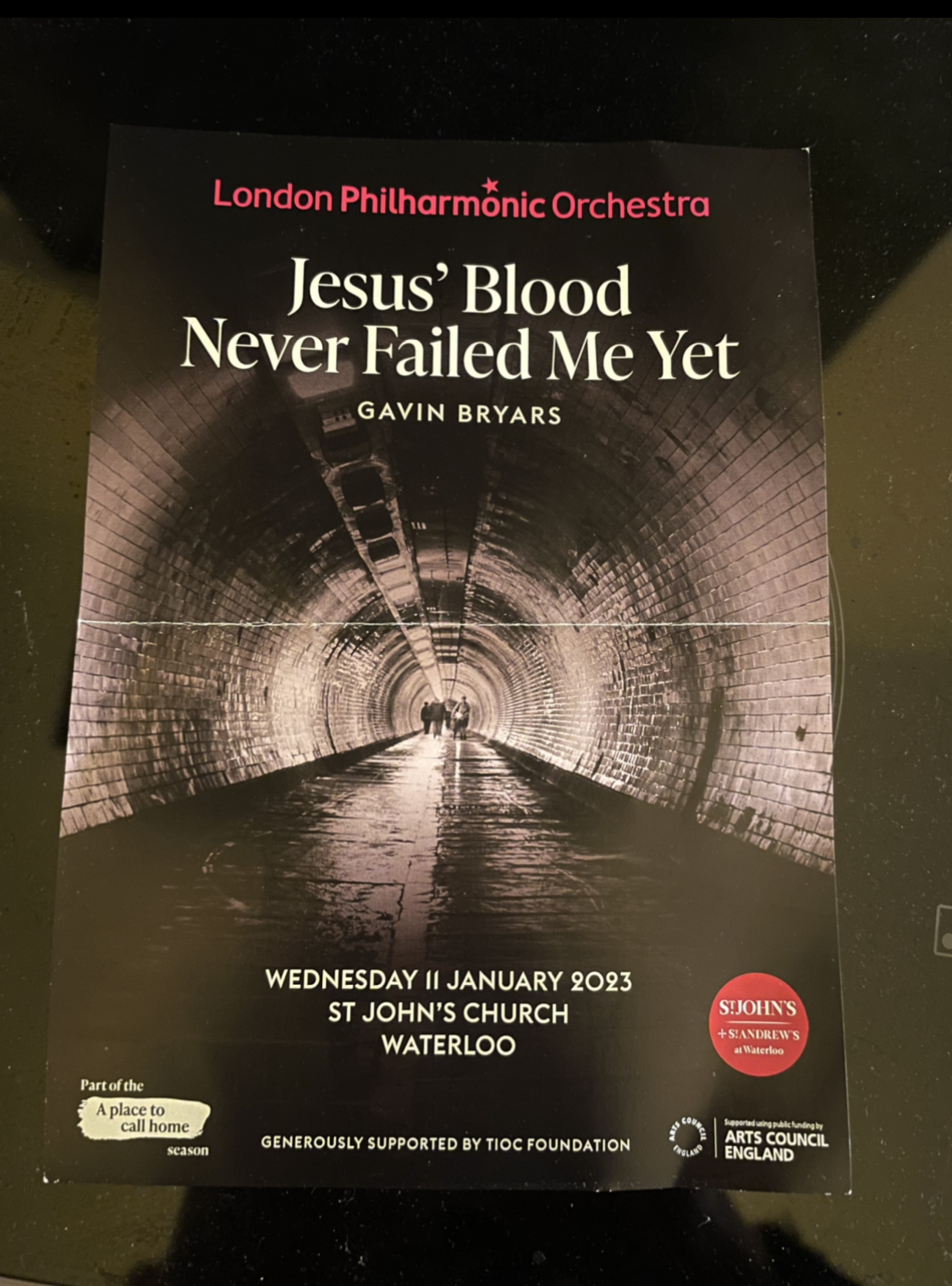

Gavin Bryars and the LPO: live in Waterloo

I promise myself I’m not going to cry. As the lights go down and the circle of musicians are illuminated, points of light emanating from their music stands, everyone falls silent.

We hear the faint quavery voice of an old man singing, hardly audible, as if from the bottom of a well. The voice becomes a little louder, a little closer, moving towards the top of the well, until we can make out the full song, lasting just 26 seconds.

‘Jesus’ blood never failed me yet,

Never failed me yet,

Jesus’ blood never failed me yet,

This one thing I know

For he loves me so’.

There is something so poignant about the man’s phrasing, the space between ‘me’ and ‘yet’, the gap somehow highlighting the man’s faith that Jesus’ blood never will fail him. His voice rises in a querulous, hopeful way to the top of the phrase ‘this one thing’, then drops down. When he sings ‘for he loves me so’, I feel the old man’s faith again in his words, in his song.

At the beginning of the piece, the man sings the phrase unaccompanied, on a loop. Introducing the work that evening, the composer, Gavin Bryars, tells us the story of how he discovered this song.

In 1970, a friend of his, Alan Power, was working on a documentary series about the homeless people who lived around Euston, Waterloo and Elephant and Castle in London.

An old Routemaster bus parked up in Waterloo, near the venue

The documentary maker gave Bryars the unused sound recordings from his research. Back then, recording tape was expensive, so he was happy to have the tapes. But before he recorded over them, he listened to them.

He was struck by the song sung by one homeless man: Jesus’ blood. He realised that the man was singing in tune and resolved to augment the song.

Influenced by John Cage and Miles Davies, Bryars had an experimental approach to making music. He decided to make a loop of the recording and took the tape to the studio where he was working in the Fine Art department at Leicester Polytechnic. He copied the tape onto a continuous reel of tape, leaving it on the machine with the door to a painting studio ajar.

He went out for a cup of coffee and came back to find his students strangely subdued. Some were crying. Somewhat stunned, he realised that the students had been overwhelmed by the sound of the old man’s voice.

Convinced by the emotional power of the music, he decided to add an orchestral accompaniment that respected the homeless man’s nobility. Something that would be testimony to his spirit and optimism.

No one ever found out the man’s name. He didn’t appear in the documentary and there was no footage of him. Someone remembered that he was elderly, that it didn’t look as if he had long to go. He was the only non-drinker of the group.

And so we are listening tonight to musicians from the London Philharmonic Orchestra accompanying the voice of an unknown man who probably died 50 years ago. He never knew his recorded voice would live on in a composition; he never knew how many people his voice would touch. It’s an extraordinary story. A tiny relic gathered by chance, polished and preserved. A homeless man’s song amplified and shared around the world.

Since composing the original piece in 1971, Bryars has created many different versions. At 30 minutes long, this one is close to the original.

After around four minutes of listening to the unaccompanied song, I watch as the string players to my left pick up their bows and draw them so softly across the strings that barely a sound emerges.

Too late, I feel a tear on my cheek. I hold my breath and let the tear drip, wondering if it will dry, if anyone will see. Remind myself that it’s dark and no one cares whether anyone is crying. Unless someone is up on the balcony, looking out for tell-tale glistening cheeks, the surreptitious wiping away of tears.

My mother’s dementia is worsening and I am open to grief, feeling the loss of the person she once was. Two nights earlier, I’d listened to the whole of Jesus’ Blood on YouTube and cried a torrent.

The strings steadily increase their volume, with the old man’s voice still the star. Bryars had told us his intention was always for the instrumentation to be in service to the voice, never overwhelming it.

Watching the double bassist elegantly pluck one string, then another, I relish the pizzicato, echoed by a couple of notes on a guitar. I wonder how I’d feel playing those few notes over and over for 15 minutes. I imagine it would feel like a privilege.

I’ve been in this church several times before, most recently when I was playing the harp with the London City Orchestra. I remember a rehearsal of Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony here, a concert featuring Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances and another where we played Sibelius’ First Symphony, one of my all-time favourite harp parts.

St John’s church in Waterloo is known for its support for the homeless

The church is right by the IMAX cinema on the roundabout. It’s a church with a long tradition of supporting people who have become homeless. The evening is part of the LPO’s ‘A place to call home’ season.

Bryars also mentioned that every year Jesus’ Blood is performed at St Martin’s in the Fields in remembrance of the homeless people who have died in the previous 12 months.

The musicians are seated in a circle, with the instruments arranged more or less in the order in which they play.

Over to my left are the strings – violins, cellos, double basses, with a guitarist next to them. Opposite me, the woodwind – flutes, oboe, clarinet, bass clarinet and bassoon. On the far side of the circle, four horns, followed by the brass – trumpets, trombones and a tuba. A sole oboist sits next to a glockenspiel player. Directly in front of me is the harpist, Rachel Masters. To her left, a keyboard player closes the circle.

The woodwind join in, with long sustained notes across the bars, adding subtly to the texture.

To me, the emotional heart of the piece is when the brass start playing, first the horns, then the trumpets, trombones and tuba. This has something of the grandeur of a brass band, like the Salvation Army playing at a sixteenth of normal speed. This is Bryars paying tribute to the faith and nobility of a man who sings to us from a distance of over half a century.

The harp adds slow rising notes to the mix, finishing with harmonics that add delicate translucent notes to the end of the phrase.

After waiting for maybe 25 minutes, the glockenspiel player finally stands up, holding two soft sticks in each hand, and adds resonant chords.

The brass mute their instruments, the tuba player using a giant black cone the size of an elephant’s foot and, imperceptibly at first, the music starts to fade out. The man’s voice holds out until the last, detectable above all the instruments until they all quieten to nothing and the piece ends.

This was beautiful. Thank you Gavin Bryars. Thank you LPO. Thank you to the unknown man who sang for us. You touched our souls and gave us hope.

More

I’m a professional writer who plays the harp in her spare time. Find out more here: