Celebrating Ethel Smyth: composer and Suffragette

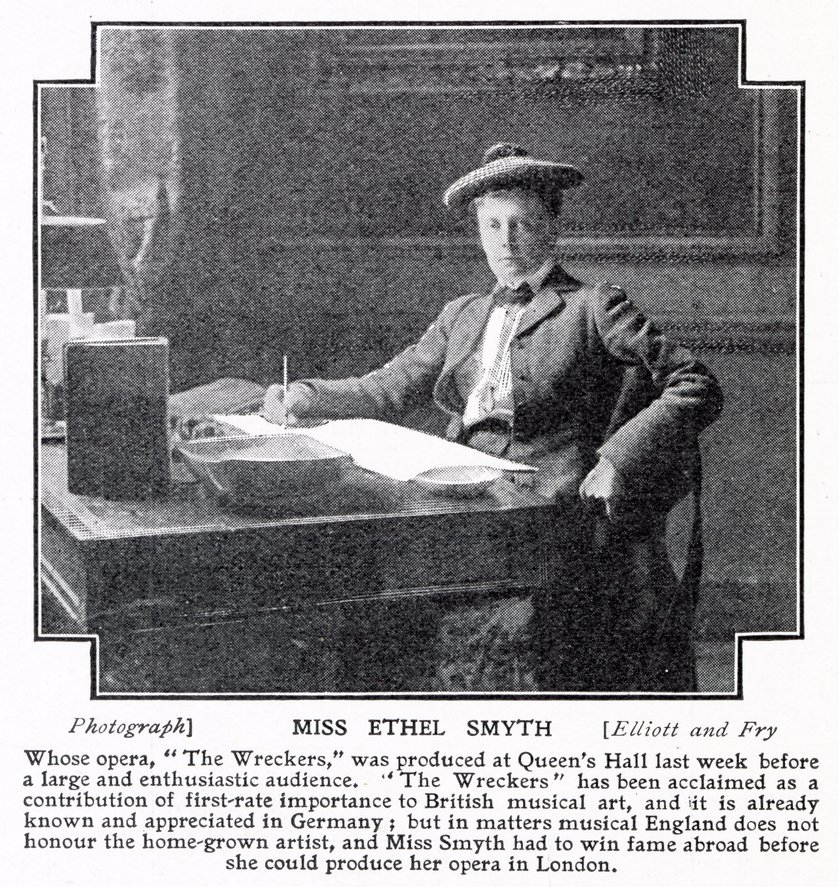

When you look at photos of composer Ethel Smyth from the early 20th century, she cuts a distinctive figure. Iconoclastic, queer and a Suffragette, she had to fight to have her compositions heard at a time when female composers were relegated to musical footnotes.

Conducting with a toothbrush

My favourite story about her is the time when conductor Sir Thomas Beecham saw her in Holloway Prison. She was locked up next to Emmeline Pankhurst, after the two of them had broken windows at the Houses of Parliament as part of a Votes for Women Campaign.

Beecham arrived in the courtyard of Holloway Prison to witness a “noble company of martyrs marching round it and singing lustily their war chant, while the composer, beaming approbation from an overlooking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush”.

Hear the overture to The Wreckers on 18 March

I became interested in Ethel Smyth because I’m playing in the overture to The Wreckers, one of Smyth’s operas, in a concert with the London City Orchestra on 18 March. We’re also playing a little-known violin concerto by 2oth century Welsh composer Grace Williams as well as Mahler’s First Symphony. You should come. (Tickets are here.)

Here, Dr Amy Zigler, Associate Professor of Music at Salem College and a scholar of Smyth’s works, shares her thoughts about the composer, her achievements and our orchestra’s upcoming programme.

What made you want to study Ethel Smyth’s music?

Smyth was initially a summer research project in graduate school. I first encountered her extensive biography – she had met Queen Victoria, she knew Brahms and Tchaikovsky, later she knew Virginia Woolf. As well, she had achieved all the things a composer hoped for – premieres and publications of her music, and in many cases repeat performances. I admired her ambition and, frankly, her stubbornness. She knew what she wanted, and she worked hard to achieve it. And yet, I (like so many others) had never heard of her, and I wanted to know why.

The first music I heard was a 1930 recording of the overture to The Wreckers … and it wasn’t very good. The recording wasn’t remastered and was ‘pitchy’ and jaunty in comparison to today’s performances and interpretations. I think that affected my initial impression.

Ethel Smyth’s opera, The Wreckers, was inspired by stories of shipwrecks on the Cornish coast

I like the overture much better now, especially having seen the opera three times. It makes sense in a way that didn’t the first time.

Back then, though, I was sceptical – how could I research a composer whose music I didn’t like? But I kept listening, and I discovered her chamber music, her Serenade in D, and the prelude to Act 2 of The Wreckers, “On the Cliffs of Cornwall”. I found the Violin Sonata, Op. 7 especially moving, even more so from my point of view as a pianist. Then, I discovered that no one had written about her chamber music – and that became my dissertation.

Since then, I’ve heard most of her music, either through recordings or live performances. It is emotionally expressive, at times powerful, at other times quite poignant, and often dramatic.

I’m also interested in how her music is a reflection or expression of her own life. Her operas and songs are rife with potential interpretations. With her instrumental music, that’s not so obvious, but the investigative work is part of the fun. Researching obscure references to Dante or Dickens, sifting through letters, and trying to understand why she wrote a piece of music, for me, brings her music to life.

How did her character and approach to life come through in her music?

If one reads her memoirs or her letters, one gets a sense of a larger-than-life personality. She wasn’t afraid to knock on a conductor’s door, or to pull her music when she wasn’t happy with a performance. That dynamism, assertiveness, and even urgency comes through in passages like the Gloria of her Mass in D, or the last movement of her Cello Sonata, Op. 5. She also cared deeply about the people in her lives, and her passion can be heard in the love duet in The Wreckers, for example. She was also quite a voracious reader and had lengthy philosophical discussions with her librettist Henry Brewster; that introspective part of her can be heard in the third movement of her String Quartet in E minor, or the opening to The Prison.

How difficult was it for her to have her music heard?

She would say it was extremely difficult! But in reality, Smyth was able to get performances of everything she published. The real difficulty came in securing repeat performances. Many of her compositions were performed once or twice over the course of her career, with only a handful performed several times in multiple cities.

Why do you think her music is starting to be appreciated more now?

In part, I think it’s because more people are exposed to it than have been in the last 70 years, through concerts and recordings. As well, a few conductors have devoted significant time and resources to her music in recent years, including Leon Botstein, Odaline de la Martinez, James Blachly, and John Andrews amongst others. That endorsement carries a lot of weight.

I also think recent events or cultural shifts have encouraged a rediscovery of her music. One is the centennial of the Suffrage movement, which took place in 2018 in the UK and in 2020 in the USA. For orchestras looking to program a piece connected to the Suffrage movement, Smyth was the perfect choice. The second is a shift in the last five years or so among musicians and audience members alike toward an openness to new music and a willingness to judge it on its merits, rather than immediately dismiss it if they’ve never heard of it.

At the end of the day, it comes down to the music. Audience reaction has been very positive at the concerts I’ve been to, with most wondering why this music isn’t played more often. Her music is powerful, dramatic, sublime and at times playful. It’s wonderful music to experience live.

What makes the overture to The Wreckers such an interesting piece?

The opening ‘Wreckers’ motive is invigorating, performed by the full orchestra, with the sparkle of the winds and the power of the brass and percussion. Then there is the crash of the waves on the rocky shores, followed by a Cornish melody. There is tension and apprehension as themes are hinted at but not fully stated. She takes advantage of the different colours of the English horn or a solo violin or a muted trumpet. And then there’s the beautiful chorale writing that alludes to the religious setting of the work. Smyth has captured the most important elements of the story in this 10-minute overture – the zealotry of the community, the yearning of the hero and heroine, the dramatic triumph of love and righteousness.

If people enjoy the overture, which of Smyth’s compositions should they listen to next?

Definitely “On the Cliffs of Cornwall”. After that, I would recommend an earlier piece and a later one – the Violin Sonata, Op. 7 (1887) and the String Quartet in E minor (1912). If they are interested in her works for voice and orchestra, I would highly recommend The Prison (1930).

Where would you place Smyth in the canon of composers?

This question is difficult to answer because it depends on the composition. Her early works are influenced by Brahms and the German ‘masters’, with an emphasis on form, counterpoint, and thematic and motivic development. The Mass in D is indebted to Beethoven and Verdi. Her first three operas are in the late Romantic style and demonstrate her familiarity with Bizet, Wagner, and Tchaikovsky, while asserting her own voice. The Wreckers in particular foreshadows Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes. Her works after WWI should be included in discussions of the English Musical Renaissance and the music of Elgar and Vaughan Williams.

I think she’s an important voice in England at the turn of the century, and we are only now starting to assess her place in the canon.

What do you think of the LCO programme that features the overture to The Wreckers alongside Grace Williams’ violin concerto and Mahler’s First Symphony?

For me there is a sonic similarity – each composer takes full advantage of the orchestrational possibilities, highlighting the different colours and instruments, from the piccolo to the tuba to the tambourine.

Curiously, all three composers also quote folk songs or allude to traditional material in these works. Smyth alludes to Protestant church music in her ‘revival theme’, where she incorporates ‘intervals familiar to all who know our own folk-music’, which she wrote in the preface to the 1909 libretto. Mahler famously quotes ‘Frère Jacques’ (or ‘Bruder Martin’, as he called it) in the third movement. Williams quotes a Welsh folk song, ‘Hen Ddarbi,’ in the second movement of her concerto. But none of them merely quote material; instead, this material is used to generate new material in truly creative ways.

I find these pieces exciting and intriguing, and to hear them live in the context of each other will make for a rewarding experience.

More:

- Book tickets for the London City Orchestra concert featuring Smyth on 18 March

- Contact Dr Amy Zigler on Twitter – @Dr_Amy_Zigler

- See the official Ethel Smyth site

- Read this BBC piece on Ethel Smyth (my source for the toothbrush story)